"Colombia arrests 25 illegal migrants from Eritrea and Nepal who illegally entered the South American country and intended to board a boat to cross the Gulf of Urabá, in northwestern Colombia, at night in transit to Panama." See more

Cyclic transcontinental mixed migration flows have triggered humanitarian emergencies in Colombia. These cycles of humanitarian impact are driven by increased flows of refugees and migrants transiting through Colombia and backups at border entry and exit points. There has been ongoing migration flows from Haitisince the 2010 earthquake, as well as countries in Africa and Asia. However, since 2014, these cycles have intensified, with refugees and migrants coalescing in municipalities surrounding the Gulf of Urabá.

"Colombia arrests 25 illegal migrants from Eritrea and Nepal who illegally entered the South American country and intended to board a boat to cross the Gulf of Urabá, in northwestern Colombia, at night in transit to Panama." See more

Thirty-five immigrants, mainly from Nepal and India, were detained in the rural village of Belén de Bajirá in the Urabá region of Antioquia.

The people were being transported through Urabá to enter Panama illegally. The immigrants were passing through the rural area of Belén de Bajirá in Mutatá when the police detained them. These individuals, all male, were being transported in a truck bound for the jungle of Chocó, where they would attempt to reach Panama as a means of entering the United States." See more

"Enfan is from Sri Lanka, in South Asia. [..] – "The war there is not over. We Muslims are still being persecuted, and they want to kill us," he says. Enfan maintains that his destination is not Colombia but the United States, where he will seek refuge if his flight is successful. Enfan's story is repeated in other eyes, in other nationalities, and other languages. The thousands of migrants that, in recent years, the inhabitants of this corner of Colombia have seen pass through." See more |

"For the most part, the migrants entered the country irregularly through Nariño, headed towards the Gulf of Urabá through Antioquia, before seeking passage to Panama through the bordering municipality of Sapzurro. The aim of this whole journey was to reach North America. On many occasions, they breached border closures that countries such as Ecuador, Panama, and Colombia had implemented at the beginning of the year due to the covid-19 pandemic. The situation worsened as they were refused tickets to cross legally, and there was the presence of illegal boats. Commenting on this illegal transportation, Juan Francisco Espinosa, director of Migración Colombia, warned at the time that "facilitating the mobility of irregular migrants is irresponsible and puts families and individuals at risk." See more

This situation becomes more visible when pressure on public and social services is critical, and protection risks lead to human tragedies. Observations of news outputs from 2010 to June 2022 show the irregular pressure cycles in the media (which reflect the pressure felt in regional contexts). In 2021, media coverage of the migration intensified as flows backed up due to government restrictions on international movement to curb COVID.

Number of national media reports on Haitian and African migrants in Colombia

No Data Found

The flow of mixed transcontinental movements through Colombia has been going on for decades but soured between January and September 2021. More than 88,500 people crossed the border from Colombia to Panama through the Darién Gap. In July, a humanitarian crisis began unfolding due to the arrival of over 1,000 people per day (on average) in the municipalities of Necoclí (Antioquia) and Acandí (Chocó).

These migratory flows come from third countries, consisting of Haitians, Africans, and individuals from several Asian countries such as Bangladesh. However, according to Panamanian migration authorities, as of 2022, Venezuelansmake up the largest group crossing the Darien Gap.

Recorded by the Panamanian migration authorities (SENAFRONT)

No Data Found

Through media coverage and reports from the field offices of Forum organizations, several routes used between 2021 and the first half of 2022 have been identified mainly. At least eight routes intersect with different means of transport.

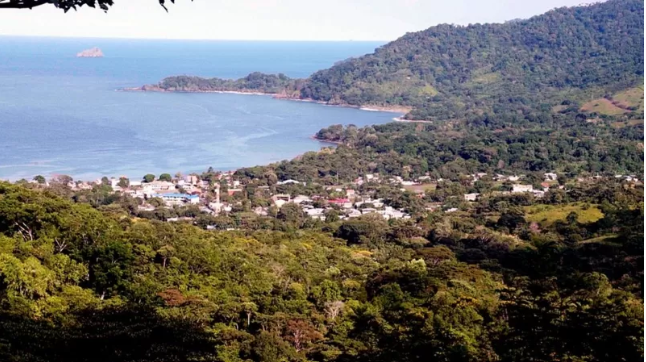

From Colombia's interior, migrants typically head for the Gulf of Urabá, as from there is the shortest route through the coastal or jungle area to La Miel, Limón, or Yaviza, all in Panama. Caritas identified that, given the increase in roadblocks and backups in Necoclí, some use other routes through the department of Chocó, such as through Riosucio, Jurado, and the Salaquí or Truandó rivers.

Likewise, Facebook connection tracking (tooltip) and organization responses indicate that some other routes or variations have not been documented nationally. For instance, the route starts in Ipiales and moves towards Pasto and Popayan, as well as backup points in Norte de Santander, Santander, and Boyacá that may indicate another unknown route.

According to the quantitative information gathered by Forum organizations, the profile of those undertaking this journey differs from that of Venezuelan refugees and migrants. This affects the likelihood of gaining access to goods and services, protection risks, and specific humanitarian needs.

At the peak of migratory flows in 2021, when the migrant population intending to cross the border into Panama was at a standstill, 48,000 Facebook connections were identified amongst Haitians and Africans in 45 municipalities.The following dashboard shows the connections and their national distribution from that moment onwards.

This dashboard is updated every two months as long as the number of connections allows it. By reducing the number of connections and the number of municipalities, the population in the territory may be oversized, so this period is omitted.

In September 2021, two rapid humanitarian needs assessments based on the MIRA methodology were conducted by Humanitarian Country Team partners, led by the Humanitarian Advisory Team - HAT (OCHA Colombia). These assessments were carried out in Acandí, Capurganá, and Necoclí. However, the same form was not used for both collections. Therefore, some results are presented for Necoclí and not for Capurganá or Acandí and vice versa.

Most of those interviewed (MIRA incorporates key informant interviews) at the peak of the refugee and migrant bottleneck in the Darien Gap were Haitian (77%), followed by a smaller number of Venezuelans (8%).

Most of those interviewed (78%) had traveled with children in their groups. According to a report, 4% of the population has some kind of limitation or disability.

No Data Found

Transiting families typically comprise between 3 and 4 people. However, amongst those interviewed, there are families of up to nine as well as lone travelers transiting in groups.

Most of the population interviewed (88%) indicated that they entered Colombia through Nariño, mainly Ipiales, and to a lesser extent through Norte de Santander (6%) and Arauca (2%). Five percent of people do not know which department or municipality they entered Colombia through.

No Data Found

This indicates that most refugees and migrants come from second countries rather than their country of origin, except Venezuelans who enter through the shared border. People interviewed in Acandí and Capurganá reported that they mostly came from Chile (61%), but three in ten preferred not to say. Sixty-two percent transited through Ecuador as the last country to enter Colombia, often passing through Peru. Six percent left Brazil, 4% crossed through Brazil as their last transit country before reaching Colombia, and 1% left French Guyana and entered Colombia through Venezuela.

Likewise, at 34 days, refugees and migrants spend a little over a month on average transiting through Colombia, according to experiences gathered through interviews. However, 22% of those interviewed had been in Colombia for longer. One respondent even reported that transit took more than a year because of the pandemic.

Moreover, beyond the transiting situation, migratory profiles are largely determined by the reasons for leaving their country of origin. Across the board, the most common reason was a lack of economic opportunities. Indeed, for some countries, the majority of those interviewed indicated that this was the most relevant cause, including people from Ecuador, Angola, and Bangladesh.

However, for others, the reasons were more multifaceted. While many Ghanaians and Cubans also stated a lack of economic opportunities, many also pointed to their country's security situation as another reason for leaving their countries of origin.

For Venezuelans, both the lack of economic opportunities and barriers to accessing essential goods and services were mentioned.

No Data Found

Although around half of the refugees and migrants from Haiti were seeking better economic opportunities, many other popular reasons included the security situation, the impact of natural disasters (possibly the 2010 earthquake), and barriers to goods and services.

Finally, most Congolese stated that their departure was a consequence of the armed conflict and the security situation and, to a lesser extent, the need for economic opportunities.

As a region crawling with illegal armed groups, often committing physical and sexual violence against those in transit, and dangerous boat trips, the Darien Gap is the riskiest stretch of the route through Colombia. In response, the Humanitarian Country Team's strategy focused on informing refugees and migrants about the risks faced on the journey to discourage them.

Eight out of ten of those interviewed in Necoclí thought the lack of information, for example, concerning their current situation or what lies ahead, to be a severe problem. Likewise, among people interviewed between September and October 2021, 42% thought they were underinformed about their next steps through the Darien Gap, while 38% stated that they were very well informed, 15% uninformed, and 5% did not respond.

No Data Found

At that time, the primary sources of information were friends, neighbors, and relatives (who are not necessarily other migrants), followed by the internet and social media, and traditional media (newspaper, internet, or television).

No Data Found

To a lesser extent, they consider humanitarian personnel, community members, or other migrants who are not part of their close circle as information sources.

When asked about the essential information they need, most respondents (61%) answered that they require information about the route and destination, including information about protection and deportation risks. Twenty-three percent of those questioned considered the location of assistance points along the route to be the most important information, and 16% thought that the most relevant information concerns the price of transportation and other goods and services, such as lodgings and food.

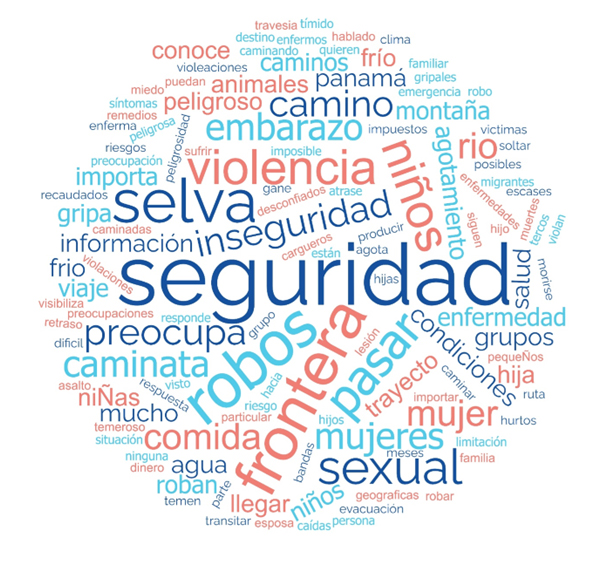

Among the people interviewed in Acandí and Capurganá, security, the jungle, and different forms of violence on the border were often mentioned as the main concerns regarding the journey ahead.

In terms of main water sources, there is no data for Necoclí, but there is for Capurganá and Acandí. For both places, the main water source is street sellers, followed by plumbed water. In Acandí, three of the informants indicated they had no water access. One of the informants also mentioned rivers and streams, and for Capurganá only, rainwater collection.

No Data Found

As seen in the health section, medical care needs and travel-related foot injuries are connected to Acute Diarrheal Diseases (ADEs), which are often associated with the consumption of unsafe water.

In Necoclí, 84% of the people interviewed indicated a severe problem because they do not have enough safe water for drinking or cooking.

In Acandí and Capurganá, 54% of those interviewed indicated that their families could not access sufficient water during the journey and considered dehydration a risk.

Regarding access to adequate sanitation, 38% of the people felt that easy and safe toilet access is a severe problem. In Acandí and Capurganá, about half of those interviewed (48%) think personal hygiene is a severe problem as there is not enough soap or water or an appropriate place to wash.

Half of the respondents (50%) thought that access to adequate medical attention is a severe problem in the migrant and refugee community transiting Colombia. This proportion is higher among people in Capurganá, where 83% of informants reported this situation.

Is accessing adequate medical care a severe problem in your community, for example, treatments, medicines, or medical care during pregnancy or childbirth?

No Data Found

In terms of pre-existing illnesses during transit, Diabetes, Asthma, Epilepsy, and Obesity were frequently mentioned, and 88% said that they have some medical need due to the journey, the most common being acute diarrhea–possibly related to water quality (35%). Twenty-eight percent have foot injuries, 14% reported respiratory symptoms (possible ARI), another 14% mentioned a combination of respiratory infections and acute diarrheal disease, and finally, one person mentioned having Zika during the trip.

Among those interviewed in Necoclí, 10% considered COVID-19 infection a health concern among refugees and migrants in transit. Fifty percent of those polled in Acandí and Capurganá reported that they had neither COVID symptoms nor tested positive, with 36% unsure. Only 2% reported having had COVID during transit.

However, based on the information from Forum organizations and other organizations in the region, the most requested care among those arriving in Nariño at Ipiales's transport terminal included "care for pregnant women, pathologies such as infectious diseases, muscle disorders, and many suspected Covid- 19 respiratory symptoms that have even required referral to the Civil Hospital in Ipiales" [Doctors of the World France report, Sept. 2021], especially in the latter half of 2022.

There are many reasons why those in transit do not report their infections or symptoms. As explained, many people leave their host countries for a third country because of waves of discrimination. The fear of additional restrictions on transportation, ticket purchasing, or care sways people not to report these situations.

Fourteen percent report being vaccinated, especially those in transit from Chile or Uruguay.

Regarding mental health, 21% of the people interviewed in Necoclí reported a severe mental health problem among refugees and migrants in transit. Thirty-six percent of the key informants said they require specialized medical attention to cope with their current situation.

Among those interviewed, 17% reported that their household eats three times a day, and 5% preferred not to answer. For those eating fewer meals per day, 8% said less than one meal per day in their homes, a more critical situation for refugees and migrants in Capurganá, where 17% reported this situation.

Twenty-nine percent reported having only one meal a day, and 42% two meals a day.

Over the last seven days, how many meals has your household consumed per day?

No Data Found

The main barrier to accessing food for respondents is a lack of resources (36%), followed by high prices (27%). Those in transit perceive that the local community increases costs intentionally because they know that migrants and refugees travel with their savings. Other difficulties are also mentioned, such as being unable to cook their own food as they have nowhere to do so and challenges around communication due to language barriers.

What are the main barriers to accessing food?

No Data Found

The people interviewed in Capurganá pointed to the risks of going to the market as a barrier to accessing food.

For 68% of the people interviewed, there had been a significant change in the amount of food they consumed before starting the journey compared to the time of the interview; 21% preferred not to answer this question. Only eight percent felt that they consumed the same amount during the transit as before starting out. Three percent reported consuming more food than before transiting.

The most frequent coping strategy is borrowing money (21%), followed by begging in the street or on a beach (14%). Also, 8% of the informants had to sell their goods, and 8% bought on credit or borrowed food. Seven percent report having accepted risky jobs or activities. Seven percent reported having accepted risky employment or activities.

Reports of family separation were commonplace, often resulting in unaccompanied children and adolescents. The two main reasons include adult health, whereby they cannot keep up with the group, or logistical reasons.

Forty-one percent reported separation as a severe problem, as family members have become separated. Twenty-six percent indicated that the separation occurred when leaving the country of origin, and 14% stated that the separation came about during the journey.

Of the people interviewed in Necoclí, 73% consider a lack of awareness of legal rights a severe issue. This was not asked in Acandí and Carpuganá.

In terms of security risks, on top of those mentioned in the water and food security sections, respondents were asked about the occurrence of violence. Due to the wider context and permanence and even temporariness of those in transit and the experiences during the route, these questions do not reflect the magnitude of the situations of lack of protection and violence they may have faced. Often, as shown in the section on access to information, the fear of sexual violence based on the experiences of other migrants shared in the media is also an indicator of what is happening along the route and is unknown.

Only 2% of the people interviewed in Capurganá and Acandí consider that they have access to timely information about their legal rights and access to care should they become victims of violence.

When analyzing this transcontinental migration through Colombia, it is essential to bear in mind that, according to the ICRC, there are six ongoing armed conflicts in Colombia, heightening the risk for those embarking on this journey through the country.

According to the information gathered, 25% of the people affirmed that most children and adolescents attended an educational institution before starting their transit.

According to 61% of the people interviewed, a lack of and inadequate lodgings is a severe problem in these municipalities. Those interviewed (52%) reported that refugees and migrants mainly stayed in paid accommodations (lodgings, motels, hotels, etc.).

Followed by the beach situation (39%), , which refers to when people either stay on the beach or set up hammocks under piers. It is the same as being homeless since they have no place to shelter from bad weather.

Thirty-three percent of those interviewed mainly stayed in planned or improvised shelters, and 14% lodged in houses belonging to the host community. The rest preferred not to respond.

Those interviewed in Acandí and Capurganá expressed that people’s main needs are, to reach their destination soon (26%), food (20%), safe transportation (20%) and drinking water (8%) among other needs (protection, information, medical care, toiletries, shelter, sanitary facilities and financial services to receive remittances).

Although 78% of the people interviewed traveled with children and adolescents, there is no information on this demographic’s nutritional situation or on pregnant womenThis information gap prevents the humanitarian response from reaching this group and their specific needs. Likewise, there is a lack of information concerning access to emergency education or protective spaces for children and adolescents along the route. This information is instrumental in identifying the most urgent needs, not only during the transit in Colombia but also for the other countries in the region.

In Colombia, two coordination bodies manage the humanitarian response. The first is the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT), organized through clusters, which coordinates the response to all humanitarian situations, including armed conflict, natural disasters, COVID-19, and, until 2021, transcontinental migrant flows. It does not respond to events concerning mixed migration flows from Venezuela. The other body is the Interagency Group on Mixed Migration Flows (GIFMM as per its Spanish acronym), the R4V platform’s national body (Response for Venezuelans), led by UNHCR and IOM.

Therefore, both organizations have their own resources, projects, and teams to respond within their own frameworks. In 2021, Humanitarian Country Team coordinated the response. However, activities were often reported without including transcontinental migrants and refugees, adding to the coexistence of multiple national emergencies. It is not possible to identify the response during 2021 through the HCT monitoring body.

The visible response was concentrated in the municipalities of Darién, Necoclí, Carpurganá, and Acandí. Even among these areas, Caritas, through Europana, identified that the response was focused primarily on Necoclí due to bottlenecks. However, in the Vereda las Tecas in Acandí and the El Cielo sector in Capurganá, the same response was not being managed, and in these places, the population has less access to information.

According to the information gathered in the MIRAs carried out between September and October, 23% of those interviewed had received some form of assistance, mainly from family or friends, followed by the Church and NGOs (especially the Red Cross).

On the part of the NGO Forum's organizations, qualitative reports identified Caritas, through Europana, who delivered kits for caminantes (migrants traveling by foot) that include adequate items for the journey, as well as hygiene kits for women and babies and food. The response of World Vision was also identified through its action regarding Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in municipalities such as Bajó Baudó.

In other regions of the country, such as Nariño, other organizations, including Forum organizations, coordinated response mechanisms. Only Médecins du Monde France and Proinco delivered a response tackling healthcare issues. At the height of the emergency, at least 280 people in transit to the Darien Gap in the department of Nariño received assistance, especially Haitians.

In total, during 2021, the activities of Forum organizations reached 2,265 refugees and migrants transiting in transcontinental flows.

Due to the crisis between September and October, within the 2022 Humanitarian Response Plan , 30% of the approved projects included transiting migrants and refugees within their general plan. Four percent of the projects specifically targeted the response to this cyclical emergency.

As of May 2022, the activities of Forum organizations during the first quarter of 2022 have reached 3,934 refugees and transcontinental migrants (see more), mainly addressing Protection and Health issues.

There are multiple coordination challenges for the humanitarian response. The response to transcontinental migrants was included in the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) led by the Humanitarian Country Team.

However, due to a change in the composition of migrant groups (composition according to nationality is also cyclical), the response will now be coordinated by the Interagency Group on Mixed Migration Flows (GIFMM), mainly in the Darien Gap. This process is in transition.

Caritas Germany and Médecins du Monde (France), with iMMAP’s information management support, participated in developing this product.

For more information, contact: ihurtado@immap.org

Última fecha de actualización 18·07·2022